During an 18-month stretch in 1986-87, Frank Miller had a number of comic series published that many creators would be pleased to list as their career output, including Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, Daredevil: Love & War, and Elektra Assasin. Two of the storylines published in this period were done in collaboration with artist David Mazzucchelli, Daredevil: Born Again and Batman: Year One, both of which could be argued as the best superhero comic story every published. (Dark Knight is in that conversation too, but we're here to discuss Miller/Mazzucchelli). What these two artists achieved is impressive. What they were allowed to do with mainstream characters seems impossible. And the limited track record these two had, prior to 1986, makes it all the more improbable.

Miller debuted as an artist for Marvel comics, in the late 1970s, doing fill-ins across a number of titles. He landed a regular art assignment on Daredevil, in 1979, and was promoted to full scripting duties, while still penciling the series, toward the end of the following year. Miller wrote 27 issues of Daredevil, garnering critical acclaim along with improved sales, for a title that was nearly cancelled before and during Miller's tenure. After this, Miller drew another half dozen or so comics, including Chris Claremont's Wolverine mini-series, until Ronin, the next project he wrote and drew, a six-issue series published as squarebound, 52-page books by DC Comics. And with that, Miller's writing résumé leading into this year-and-a-half burst of creativity was complete.

Mazzucchelli, similarly, had a limited résumé leading into these two significant storylines -- Born Again and Year One. Mazzucchelli drew a half dozen individual issues across various Marvel titles like Star Wars, Marvel Fanfare, and X-Factor. Then in 1984, with issue #206, he became the regular artist on . . . Daredevil, roughly five years after Miller had done the same. From there, Mazzucchelli drew through issue #217 (missing #207) and then #220-226 (missing #224), or 15 total issues. At the point the Born Again storyline commenced, Mazzucchelli hadn't drawn the equivalent of two years worth of monthly comics. And yet -- in conjunction with works by the likes of Alan Moore and Art Spiegelman -- he and Miller were about to change the face of comics.

The most important thing to remember about Born Again and Year One is the fact that these were not part of a more adult publishing arm from these Big 2 publishers, like Epic or Vertigo (still almost a decade away from inception), nor were they even outside mini-series. These two storylines took place within the regular titles of each character, Daredevil and Batman, respectively. One issue, you were reading a story from a different creative team (though Mazz was the regular artist on Daredevil at the time), the next, Miller & Mazzucchelli were bringing a whole new level of storytelling to your standard, monthly, four-color adventures: issues #227-233 of Daredevil and #404-407 of Batman. It had to be jarring for some regular readers.

The first collaboration between Miller & Mazzucchelli was at Marvel, with Daredevil: Born Again, in 1986. Miller's initial run on the character, a few years previous, had made Daredevil a more edgy character, injecting him into the shadowy crime world of New York City, while also introducing a bit of fantasy in the form of the ninja clan, The Hand, his blind martial arts mentor, Stick, and Matt Murdock's (Daredevil's civilian identity) former lover, Elektra, who had become a ninja assassin in the intervening years. Born Again expanded on that base in ways that would blow up the title, and mainstream comics, in a profound way.

The opening scene of the first issue of this storyline -- again, importantly, nestled within the regular monthly series, with issue #227 -- has Karen Page, another of Matt's former lovers, giving up the secret that he is, in fact, Daredevil, for the price of a shot of heroin (unspoken at this juncture, but stated outright later in the story). We also learn that Karen has been involved in either soft or hardcore porn, as the dealer talking with her mentions he recognizes her from her flicks, that she's "big at the stag parties." At this point, in 1986, comics were still considered fodder for children, brightly garbed heroes beating up brightly garbed villains, with a return to the status quo at the end of every issue, only for the pattern to repeat the following month. These comics, particularly superhero comics distributed to newsstands and spinner racks, like Daredevil, were aimed at this demographic; they weren't yet made with adults in mind. So, for this story to begin with a character being described as popular at stag parties and selling our hero's secret for drugs was a big deal. Certainly, drugs had been used as story points before, most notably in Green Lantern/Green Arrow #85 and the anti-drug storyline from Amazing Spider-Man #96-98. These were important milestones in the history of comics publishing, but what resulted from Karen Page's revelation would add a whole new dimension to comic book storytelling.

It's the tone of this story, by Miller & Mazzucchelli, that really stands out for me. They don't treat Karen Page's addiction with anything approaching bombast or titillation. It feels like something from a hardboiled pulp novel by the likes of Raymond Chandler or Jim Thompson, authors whom Miller holds in high regard. It is this ground level, almost subdued (when taken in the context of typical superhero comic book fare) approach that elevates the story, as we follow Karen in her flight to New York hoping to find help from Matt. She hitches a ride with a skeevy character -- a pimp who wants to use Karen, to turn her out and make himself some scratch. He keeps his hold over her by offering up the heroin she needs, even as Karen desires to be free of this addiction. But combating a drug addiction is not an easy task. It requires daily vigilance even after you kick it. This truth, along with the shadow of guilt Karen feels and the torture she endures, resonates throughout her arc.

Along with this new, adult approach to the character of Karen Page, Miller & Mazzucchelli also break down Matt Murdock, bringing him to a point as low as readers had ever seen him. Again, it is the tone of the storytelling that stands out -- no bombast or melodrama dripping with sentimentality, no overt machismo here. This feels real, genuine, a psychotic break we can believe, and it erupts into violence that is unhinged, unsettling, and unnerving. Matt believes everyone, including his former lover and his best friend, are turned against him. He sees devils everywhere he looks. When a collection of youths enter the subway car Matt is riding, intent on divesting the passengers of their valuables, and one of them points a gun in his face, Matt smiles, coldly, calmly . . . and then he reacts, taking out the armed thief, followed by his cronies, leaving them in a bloody mess on the subway car floor. As it stops, a police officer enters, gun drawn, and Matt proceeds to take him out as well. It's a bloody assault the likes of which would have been inconceivable for the lawyer-slash-hero, previously, and it accentuates the depths to which he has fallen.

There is an even more disturbing scene of violence later in the story. Ben Urich, Daily Bugle reporter and friend of Matt Murdock, is investigating the Kingpin. He goes to the city jail with photographer Glorianna O'Breen, Matt's former, and Foggy's current, girlfriend, to question Nurse Lois, one of the Kingpin's assassins who's agreed to testify. Urich is accompanied by a fellow reporter, Blanders, and officer Hegerfors, who was assigned to Urich for protection. After the prison guard, Coogan, lets them into the cell, he locks the door. Blanders and Coogan reveal themselves to be on the Kingpin's payroll, as Blanders shoots Lois and Coogan fires on Hegerfors. Hegerfors manages to return fire, killing the prison guard, but Blanders isn't done. Everything happens quickly, Urich lunges for Blanders, knocking him down before retrieving Hegerfors's pistol and whipping Blanders with it, blood flying from the grip, even as Glori continues snapping photographs. Mazzucchelli is a beast in this scene. You can feel the tension, the desperation, the fear in Ben. It permeates every panel, with the angles chosen, the body language, the facial expressions. You know this is a life or death situation, and it stops your breath. It's brilliant. And haunting.

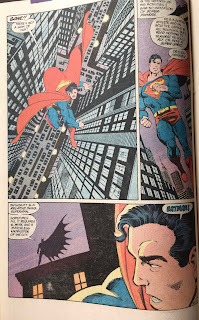

A year later, Miller & Mazzucchelli helped usher in the "new" post-Crisis Batman, with the Year One storyline in Batman issues #404-407. Again, these two creators wanted to shake things up, to infuse more "realism" into what was possible with superheroes, while, in this case, retelling Batman's origin. They also widened their net to include the origin (at least as far as his days in Gotham City) of James Gordon, a detective in this storyline who would one day become Commissioner. And it is Gordon, as well as Selina Kyle, Catwoman, whom Miller & Mazzucchelli target, in order to add to the Bat-mythos, while also dragging the comic book medium forward.

Gordon is young, but has a history in Chicago. His wife, Barbara, is pregnant with their first child, and he is hoping to restart his police career with this new posting in Gotham City. He soon learns that most of his colleagues are on the take and Commissioner Loeb is certainly corrupt (unsurprising for the cesspool that is Gotham). But Gordon is here to fight the good fight. He believes in what he does and believes he must hold to his principles. He takes out Detective Flass, a former green beret, after Flass and a half-dozen other cops roughed Gordon up to teach him a lesson. This, coupled with the good press Gordon receives for his police work, provides him with a bit of armor against retaliation by the Commissioner and his cronies. But it is still lonely, being one of the very few good cops in Gotham, and a romance blossoms between Gordon and fellow detective, Sarah Essen. Even as his pregnant wife suffers through a stifling summer in Gotham. This is one of the heroes of this story! And yet, it feels genuine, and it imbues Gordon with a humanity (though flawed) and a relatability that he may not have evoked previously. In the end, Essen requests a transfer and Gordon and his wife begin marriage counseling, but just the idea that these heroes can have clay feet feels exhilarating, and it adds a lot to this narrative, as well as to the possibilities for future narratives from these and other creators.

We also get a new Selina Kyle (Catwoman) in this retelling of Batman's origin. She is a prostitute, a dominatrix, who works in the ugly part of Gotham. Despite this, Selina comes across as a very strong character, one who seems to have chosen her profession rather than one who is being exploited. It's a fine distinction, but certainly one that comes across in this story. When Selina decides that she and Holly, the young girl who lives with her and is starting out as a street walker, are going to leave this life, she takes down the pimp who claims to own them. Then she buys a catsuit to become a burglar, and to make a splash like this new Batman. Yet, her exploits are either mistaken as that of the Batman or she is described as his sidekick. It's frustrating for her, and only makes her more determined to succeed at this new venture. Again, Miller & Mazzucchelli imbue a character with far more humanity than had been typically done in the past (and, sadly, is still too rarely achieved in our new present, 35 years after the publication of Year One). It's a relatively simple approach, but one that wasn't often attempted up to this point, for multiple reasons.

As with Born Again, Miller & Mazzucchelli also bring a more nuanced, more real approach to the violence in this story. During Bruce Wayne's initial foray into the dark streets of Gotham, even before he's latched onto the idea of becoming a bat, he is seriously injured by a knife wound and has difficulty getting home. Bruce is not the supremely able and deadly combatant he will become; he's a neophyte going on bravado and overconfidence born of youth, and it almost ends in his death. There are more examples of this too throughout the series, of punches or kicks or bullets actually having impact, causing pain, and impairing the beneficiaries of the assault. This is no WWE wrestling match, this is real life (as real as superhero comics can get), and the consequences of violence can be substantial.

Looking back from the vantage point of 2021, it is still surprising that Born Again and Year One got the green light for publication. These two stories took recognizable, mainstream superheroes and infused a groundedness and complexity of characterization that had rarely been done before. These heroes were being written for children, their battles couldn't be muddied by the grayness of reality. Drugs? Prostitution? Infidelity? Pornography? These weren't the subjects of kids' comics, and certainly weren't character traits one would associate with the good guys. And yet, Miller & Mazzucchelli, despite lacking a breadth of experience within the comic field, were allowed to take these characters and change things significantly. And it worked. Spectacularly. And we all should be thankful that the editorial regimes at these two, large publishers took a chance on these stories, because they are easily two of the very best superhero stories ever told in the comic book medium.

-- chris